General operating

Ham language

- A ham is a radio amateur.

- As hams we address one another exclusively with their first name (or nickname), never with mister, miss nor misses or with a family name. This is also true for written communication between hams.

- The ham etiquette says we greet one another in our writings using

73(notbest 73normany 73), and not sincerely or other similar formal expressions. - If you used to be a CB operator, erase the CB language from your memory, and learn the amateur radio idioms (jargon, slang) instead. As a member of the amateur radio community you are expected to know the typical amateur radio expressions and idioms, which will help you to become fully accepted by the ham community.

- During your on-the-air contacts, use the Q code correctly. Avoid overkill by using the Q code all the time in phone. You can also use standard expressions that everybody understands. Some Q codes have however become standard expressions even in phone, e.g.:

| The QRG | the frequency |

| QRM | interference |

| QRN | interference from atmospherics (static crashes) |

| A QRP | a child |

| Going QRT | leave the air, stop transmitting |

| Being QRV | being ready, being available |

| QRX | just a moment, stand by |

| QRZ | who called me? |

| QSB | fading |

| QSL (card) | the card which confirms a contact |

| QSL | I confirm |

| A QSO | a contact |

| QSY | change frequency |

| QTH | the place where your station is located (city, village) |

- As well as the small number of Q codes which are commonly used on phone, there are some other short expressions that stem from CW and that have become commonplace on phone, such as 73, 88, OM (old man), YL (young lady), etc.

- Use the one and only international spelling alphabet correctly. Avoid fantasies which may sound funny or amusing in your own language, but which won’t make your correspondent understand what you are saying... Do not use different spelling words in one and the same sentence.

Example

CQ from ON9UN, oscar november nine uniform november, ocean nancy nine united nations...

- The most widely used language in amateur radio is undoubtedly English. If you want to contact stations all over the world it is likely that a majority of your contacts will be made in English language. It goes without saying though that two hams, both speaking language different from English can of course converse in that language.

- Making contacts in Morse code (CW) is always possible without speaking a single word in the language of your QSO partner.

- It is clear that the hobby can be an excellent tool for learning and practicing languages. You will always find someone on the bands that will be happy in helping you with a new language.

Listen

- A good radio amateur starts by listening a lot.

- You can learn a lot by listening but be careful, not all you hear on the bands are good examples. You will certainly witness a lot of incorrect operational procedures.

- If you are active on the bands, be a good example on the air and apply the guidelines as explained in this document.

Use your callsign correctly

- Instead of callsign or call letters, hams usually employ the short form call.

- Use only your complete call to identify yourself. Don’t start your transmission by identifying yourself or your correspondent by your or his first name (e.g.

hello Mike, this is Louis...). - Identify yourself with your full callsign, not just the suffix! It is illegal to just use the suffix.

- Identify yourself frequently.

Always be a gentleman

- Never use abusive terms, stay polite, courteous and gentle, under all circumstances.

- George Bernard Shaw once wrote:

There is no accomplishment so easy to acquire as politeness and none more profitable.

On the repeater

- Repeaters serve in the first place to extend the operating range of portable and mobile stations on VHF/UHF.

- Use simplex wherever possible. Using repeaters to make contacts between two fixed stations should be an exception.

- If you want to talk via the repeater while it is already in use, wait for a pause between transmissions to announce your call.

- Only use the term

breakor even betterbreak break breakin an emergency or life-threatening situation. Better is to saybreak break break with emergency traffic. - Stations using the repeater should pause until its carrier drops out or a beep appears, to avoid inadvertent doubling (simultaneous transmission) and to allow time for new stations to identify. Pausing usually also allows the timer to reset, avoiding a time-out.

- Do not monopolize the repeater. Repeaters are there not only for you and your friends. Be conscious that others may want to use the repeater as well; be obliging.

- Keep your contacts through a repeater short and to the point.

- Repeaters should not serve to inform the XYL that you are on your way home and that lunch can be served... Contacts through amateur radio concern primarily the technique of radio communications.

- Don’t break into a contact unless you have something significant to add. Interrupting is no more polite on the air than it is in person.

- Interrupting a conversation without identification is not correct and in principle it constitutes illegal interference.

- If you frequently use a particular repeater consider supporting those that keep that repeater on the air.

How do you make a qso?

- A QSO is a contact by radio between two or more hams.

- You can make a general call (CQ), you can answer someone’s CQ or call someone who has just finished a contact with another station. More on this follows...

- Which call comes first in your conversation? Correct is:

W1ZZZ from G3ZZZ(you are G3ZZZ, and W1ZZZ is the person you address). So, first give the call of the person you speak to, followed by your own call. - How often should you identify?

In most countries the rule is: at the beginning and at the end of each transmission, with a minimum of at least once every 5 minutes. A series of short overs is usually considered to be single transmission. In a contest it is not strictly necessary, from the viewpoint of the rule maker, to identify at each QSO. This 5 minute rule has come about as a requirement from the monitoring stations to be able to easily identify stations. From an operational point of view however, the only good procedure is to identify at each QSO.

- A pause or a blank: when your correspondent switches the transmission over to you, it is a good habit to wait a second before starting your transmission, in order to check whether someone may want to join you, or use the frequency.

- Short or long transmissions?

Preferably make short rather than long transmissions, this makes it much easier for your correspondent if he wants to comment on something you said.

What do you talk about on the amateur bands?

The subjects of our communications should always be related to the amateur radio hobby. Ham radio is a hobby regarding the technique of radio communications in the broad sense of the term. We should not use amateur radio to pass along the shopping list for tonight’s dinner...

Some subjects which are a no no in amateur radio conversations on the air are:

- religion

- politics

- business (you can talk about your profession, but you cannot advertise for your business)

- derogatory remarks directed at any group (ethnic, religious, racial, sexual etc.)

- bathroom humor: if you wouldn't tell the joke to your ten year old child, don't tell it on the radio

- any subject that has no relation whatsoever with the ham radio hobby.

Making contacts on phone

How do you call CQ?

Sometimes before transmitting it is necessary to tune (adjust) the transmitter (or antenna tuner). Tuning should in the first instance be done on a dummy load. If necessary, fine tuning can be done on a clear frequency with reduced power, after having asked if the frequency is in use.

- What should you do first of all?

- Check which band you want to use for the distance and the direction you want to cover. MUF charts are published on many websites, and can help in predicting HF propagation.

- Check which portion of the band you should use for phone contacts. Always have a copy of the IARU Band Plan available on your operating desk.

- Remember, SSB transmissions below 10 MHz are done on LSB, above 10 MHz on USB.

- Also, when you transmit on USB on a given nominal (suppressed carrier) frequency, your transmission on SSB will spread at least 3 kHz above that frequency. On LSB it is the inverse, your signal will spread at least 3 kHz below the frequency indicated on your rig. This means: never transmit on LSB below 1.843 kHz (1.840 is the lower limit of the sideband section); never transmit on LSB below 3.603 kHz, or on USB never above 14.347 kHz, etc.

- And then?

- Now you are ready to start listening for a while on the band or frequency you intend to use...

- If the frequency seems to be clear to you, ask if it is in use (

anyone using this frequency?oris this frequency in use?). Some operators askis this frequency clear?, but asking this way may lead to confusion. It does not mean that, if a frequency is clear for one particular station, it really is a clear frequency. So, let’s find out if other stations are already using the frequency by asking:anyone using this frequency?oris this frequency in use?. - If you have already listened for a while on an apparently clear frequency, why do you in addition have to ask if the frequency is in use? Because one station, part of a QSO, who is located in the skip zone vs. your location, could be transmitting on the frequency. This means that you cannot hear him (and he won’t hear you) because he is too far for propagation via ground wave and too close for propagation via ionospheric reflection. On the higher HF bands this usually means stations located a few hundred kilometres from you. If you ask if the frequency is in use, his correspondent may hear you and confirm. If you start transmitting without asking, chances are you will be causing QRM to at least one of the stations on frequency.

- If the frequency is occupied, the user will most likely answer

yesor more politelyyes, thank you for asking. In this case you have to look for another frequency to call CQ.

- And if nobody replies?

- Ask again:

is this frequency in use?

- Ask again:

- And if still no one replies?

Call CQ: CQ from G3ZZZ, G3ZZZ calling CQ, golf three zulu zulu zulu calling CQ and listening. At the end you may say ...calling CQ and standing by, instead of ...and listening. One could also say: ...and standing by for any call.

- Always speak clearly and distinctly, and pronounce all words correctly.

- Give your call 2 to maximum 4 times during a CQ.

- Use the international spelling alphabet (for spelling out your callsign) once or twice during your CQ.

- It’s better to use several consecutive short CQs rather than one long CQ.

- Do not end a CQ with

over, as in this example:CQ CQ G3ZZZ golf three zulu zulu zulu calling CQ and standing by. Over.Overmeans over to you. At the end of a CQ you cannot turn it over to anyone as you are not yet in contact! - Never end a CQ by saying

QRZ.QRZmeans who was calling me?. It is obvious that nobody WAS calling you before you started your CQ! A totally wrong way of ending a CQ is as follows:CQ 20 CQ 20 from G3ZZZ golf three zulu zulu zulu calling CQ, G3ZZZ calling CQ 20, QRZ, or...calling CQ 20 and standing by. QRZ. - If you call CQ and want to listen on another frequency than the one you transmit on, end each CQ by indicating your listening frequency, e.g.

... listening 5 to 10 upor also... listening on 14295, etc. Just sayinglistening uporupis not sufficient, as you don’t say where you are listening. This method of making QSOs is called split frequency working. - If you intend to work split frequency, always check if the frequency you plan to use for listening is free, as well as the frequency on which you will call CQ.

- Saying

CQ from Victor Romeo two Oscar Portableis not very clear. Either VR2OP calls CQ using an incorrect spelling phonetic, or VR2O/p calls CQ and omits to add the expressionstrokewhile calling CQ. This can lead to a lot of confusion. Always use the termstrokewhen you are portable, mobile etc.

What does CQ DX mean?

- If you want to contact long distance stations, call

CQ DX. - What is DX?

- On HF: stations outside your own continent, or of a country with very limited amateur radio activity (e.g. Mount Athos, Order of Malta etc. in Europe).

- On VHF-UHF: stations located at more than approx. 300 km.

- During a CQ you can insist that you only want to work DX stations, as follows:

CQ DX, outside Europe, this is.... - Always be obliging; maybe the local station calling you after your CQ DX is a newcomer, and maybe you are a new country for him. Why not just give him a quick QSO?

Calling a specific station

- Let us assume that you want to call DL1ZZZ with whom you have a sked (schedule, rendez-vous). Here’s how you do this:

DL1ZZZ, DL1ZZZ this is G3ZZZ calling on sked and listening for you. - If, despite your directive call someone else calls you, remain polite. Give him a quick report and say

sorry, I have a sked with DL1ZZZ....

How do you make a QSO in phone?

- Assume you get a reply to your CQ call, e.g.:

G3ZZZ from W1ZZZ, whiskey one zulu zulu zulu is calling you and listeningorG3ZZZ from W1ZZZ, whiskey one zulu zulu zulu over.- We have explained why you cannot end your CQ with ‘over’. When someone answers your CQ, he wants to turn it over to you (get an answer from you), which means that he can end his call with ‘over’ (meaning ‘over to you’).

- If a station answers your CQ, the first thing you need to do is to acknowledge his call, after which you can right away tell him how you are receiving his transmission, give him your name and QTH (location):

W1ZZZ from G3ZZZ (be careful, keep the right sequence!), thanks for the call, I am receiving you very well, readability 5 and strength 8 (usually the indication on the S-meter on your receiver). My QTH is London and my name is John (not ‘my personal name’ nor ‘my personal’ nor ‘my first personal’; there are no such things as personal or impersonal names). ‘How do you copy me? W1ZZZ from G3ZZZ. Over.

- If you call a station that has called CQ (or QRZ), call that station by giving his call not more than once. In most cases it’s better not to give it at all; the operator knows his own call. In a contest you never give the callsign of the station you are calling.

- In phone we exchange an RS report, a report of Readability and of signal Strength.

- We have already said not to overly use the Q code in phone contacts, but if you use it, do it correctly. QRK means Readability of the signal, which is the same as R in the RS report. QSA means Signal Strength as the S from the RS report.

- One thing is different however, the range of the S in the RS report goes from 1 to 9, in the QSA code it goes from 1 to 5 only.

- So, don’t say

you’re QSA 5 and QRK 9(as we sometimes hear), but if you want to use Q code, say:you are QRK 5 and QSA 5. Of course it is much simpler to sayyou’re 5 and 9. On CW the use of QRK and QSA is almost non-existent. In CW only the RST report is used instead .

| Readability | Signal strength | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | Unreadable | S1 | Faint signals, barely perceptible |

| R2 | Barely readable | S2 | Very weak signals |

| R3 | Readable with difficulty | S3 | Weak signals |

| R4 | Readable with no difficulty | S4 | Fair signals |

| R5 | Perfectly readable | S5 | Fairly good signals |

| S6 | Good signals | ||

| S7 | Fairly strong signals | ||

| S8 | Strong signals | ||

| S9 | Very strong signals |

Using the word ‘over’ at the end of your over is recommended but not really a must. A QSO consists of a number of transmissions or overs. ‘Over’ stands for over to you.

If signals are not very strong and if the readability is not perfect, you can spell out your name etc. Example: My name is John, spelled juliett, oscar, hotel, november ... Do NOT say ...juliett juliett, oscar oscar, hotel hotel, november november. This is not the way you spell the name John.

In most short, so-called rubber stamp QSOs, you will describe your station and antenna and often other data such as weather info (related to propagation especially on VHF and higher) can be exchanged. As a rule it is the station that was first on the frequency (e.g. the station who called CQ) that should take the initiative to bring up subjects of conversation. Maybe he just wants a short hello and good bye contact.

Use the correct terminology when describing your station. Do not say I am working with 5 Whiskey.... This certainly is not standard ham language. Simply say: I am running 5 Watts.

Even during a stereotype QSO we often see technical discussions being developed and results of experimentation being exchanged, just as we would do during eyeball conversations. Worth mentioning as well is that many friendships have been forged as a result of radio contacts between hams. The hobby is a real bridge builder between communities, cultures and civilizations!

If you wish to QSL (exchange cards), mention it: Please QSL. I will send my card to you via the QSL bureau and would appreciate your card as well. A QSL is a postcard sized report confirming a QSO you made.

QSL cards may be mailed directly to the other station or sent via a QSL bureau. Just about all Radio Societies, members of IARU, exchange QSL cards for their members. Some stations only QSL via a QSL manager who handles the mail for him/her. Details of those can be found on various websites.

Ethics require that hams should be willing to exchange QSL cards without asking money for it other than to cover return postage charges if a direct exchange is requested.

To wrap up a QSO: ...W1ZZZ, this is G3ZZZ signing with you and listening for any other calls, or if you intend to go off the air ...and closing down the station.

You may add the word ‘out’ at the end of your last transmission, indicating you are closing down, but it is seldom done. Do NOT say ‘over and out’, because ‘over’ means you switch over to your correspondent, and in this case there is no longer a correspondent!

Typical SSB QSO for the beginner

Is this frequency in use? This is W1ZZZ

Is this frequency in use? This is W1ZZZ

CQ CQ CQ from W1ZZZ whiskey one zulu zulu zulu calling CQ and listening

W1ZZZ from ON6YYY oscar november six yankee yankee yankee calling and standing by

ON6YYY from W1ZZZ, good evening, thanks for your call, you are 59. My name is Robert, I spell Romeo Oscar Bravo Echo Romeo Tango and my QTH is Boston. How copy? ON6YYY from W1ZZZ. Over.

W1ZZZ from ON6YYY, good evening Robert, I copy you very well, 57, readability 5 and strength 7. My name is John, Juliette Oscar Hotel November, and my QTH is near Ghent . Back to you Robert. W1ZZZ from ON6YYY. Over.

ON6YYY from W1ZZZ, thanks for the report John. My working conditions are a 100 Watt transceiver with a dipole 10 meter high. I would like to exchange QSL cards with you, and will send you my card via the bureau. Many thanks for this contact, 73 and see you soon again, I hope. ON6YYY from W1ZZZ.

W1ZZZ from ON6YYY, all copied 100%, on this side I am using 10 Watt with an inverted-V antenna with the apex at 8 meters. I will also send you my QSL card via the bureau, Robert. 73 and hope to meet you again soon. W1ZZZ this is ON6YYY clear with you.

73 John and see you soon from W1ZZZ now clear (...and listening for any stations calling)

Fast back and forth switching

If you are involved in a quick back and forth conversation, involving short transmissions, you do not need to identify at each over. One must identify at least once every 5 minutes (in some countries 10 minutes) as well as at the beginning and at the end of your transmissions (can be a series of QSOs).

You can also turn it over to your correspondent by simply saying over, meaning you turned the microphone over to him/her to start his transmission. Even faster is to just stop talking and pause. If the pause exceeds 1 or 2 seconds your correspondent will simply start transmitting.

How to make QSOs in a phone contest?

- Contest is the name for a radio communication competition between radio amateurs.

- What is Contesting? It is the competitive side of Ham Radio.

- Why contesting? Contests are competitions in which a radio amateur can measure the competitive performance of his station and antennas, as well as his performance as an operator. As the English say: the proof of the pudding is in the eating.

- How to become a good contester? Most champion contesters started working contests on a local level. Like in all sports you can only become a champion through lots of exercising.

- Are there many contests? There are contests every weekend, totalling well over 200 contests every year. About 20 have the status of important international contests (ham radio’s equivalent to Formula 1 racing).

- Contest calendar: see various internet sites such as ng3k.com/Contest/.

- In most contests the competitors should make as many contacts as possible with e.g. as many as possible different countries (or States, radio zones etc.): these are the so-called multipliers which will be used together with the number of QSOs to calculate your score. Big international contests run for 24 or

- Contests are organized on most bands, HF through SHF.

- There are no contests on the so-called WARC bands: 10 MHz, 18 MHz and 24 MHz. This is because these bands are quite narrow. Contesting would render these bands too crowded to be enjoyable for other users.

- In a contest a valid QSO is made when a callsign, a signal report and often a serial number (or radio zone, locator, age etc.) are exchanged.

- Contest operating is all about speed, efficiency and accuracy. One is expected to say only and exactly what’s strictly required. This is not the time for showing you are well educated, and

thank you,73,see you lateretc. are just not said in a contest. It’s all a waste of time. - If you are new to contesting, it is advisable to first visit a contester during a contest. You can also make your first steps in contesting by participating e.g. in a field day with your local radio club.

- If you decide to try your first contest, start by listening for half an hour (longer is better) to see how the routine contesters go about it. Identify the right procedures to make fast contacts. Be aware that not all that you will hear are good examples. A few examples of common errors are discussed further on.

- An example of a fully efficient contest CQ is:

G3ZZZ golf three zulu zulu zulu contest. Always give your call twice, once phonetically, unless you’re in a big pileup, in which case you give your call just once and forget about spelling it out every time. Why is the word contest the last word in your contest CQ? Because by doing so, someone who happens to tune across your frequency at the end of the CQ, knows there is someone calling CQ contest on that frequency. Even the word CQ is left out as it is ballast and contains no added information. Assume you give your call at the end (instead of the word contest): in this case the station tuning across the frequency copied your call (he checks in his log whether he needs you or not; assume he does), but he does not know if you are just working a station or calling CQ. In this case he will have to wait one round to find out, which is a waste of time. That’s why you should use the wordcontestat the end of your (contest) CQ. - The caller should call you by giving his call just once. Example:

golf three x-ray x-ray x-ray. If you do not reply to him within a second, he will give his call again (just once). - If you copied his call, you will immediately reply as follows:

G3XXX 59001or even fasterG3XXX 591(check if the contest rules accept the short number where you leave out the leading zeros). In most contests you will have to exchange a RS report and a serial number (in the above example 001 or simply 1). That is the complete exchange; all the rest is ballast. - If you (G3ZZZ) copied only a partial call (e.g. ON4X..), go back to him as follows:

ON4X 59001. Do not sendQRZ ON4Xor anything like that. You have identified the station you want to work, so go ahead with his partial call. Any other procedure will make you lose time. Being a good operator, ON4XXX will return to you withON4XXX x-ray x-ray x-ray, you are 59012. - Never say

ON4XXX please copy 59001, norON4XXX copy 59001which is equally bad. Theplease copyorcopycontains no additional information. - Being an experienced contester, ON4XXX will come back as follows:

59012. If he had not copied the report he would have saidreport againorplease again. - This means neither

thanks 59012norQSL 59012norroger 59012, things that are often being said by less experienced contesters. - All that’s left to be done is to round off the contact as follows:

thanks G3ZZZ contest(thanks is shorter and faster than thank you). By saying this you do 3 distinct things: you end your contact (thanks), you identify yourself for stations wanting to call you (G3ZZZ), and you call CQ (contest). Utmost efficient! - Do not end with

QSL QRZ. Why?QSL QRZdoes not tell anything about your identity (call). And you want all passers-by that stumble across your frequency at the end of your QSO, to know who you are and that you are calling CQ- contest. Therefore always end withthanks G3ZZZ contest(orQSL G3ZZZ contest) or if you are very much in a hurryG3ZZZ contest(this may however lead to confusion and sounds less friendly).QSLmeans: I confirm. Don’t sayQRZbecause QRZ means who called me, unless there were more stations calling you in the first place when you picked out G3XXX. - There are of course some possible variations to this scheme, but essential to this all is: speed, efficiency, accuracy and the correct use of the Q code.

- Most contest operators use a computer contest logging program. Make sure you have thoroughly tested and tried out the program before using it in real life.

- Apart from calling CQ in a contest to make QSOs you could search the bands looking for so-called multipliers or stations you have not worked yet. This is called search and pounce. How do you go about this? Make sure you are exactly zero beat with the station you want to work (watch the RIT!). Just give your call once. Don’t call as follows:

DL1ZZZ from G3ZZZ; DL1ZZZ certainly knows his call, and knows you are calling him because you call on his frequency! - So, give your call one time. If he does not return to you within 1 second, call again (1 time) etc.

Example of a contest QSO on phone

whiskey one zulu zulu zulu contest (CQ contest by W1ZZZ)

oscar november six zulu zulu zulu (ON6ZZZ answers)

ON6ZZZ five nine zero zero one (W1ZZZ gives a report to ON6ZZZ)

five nine zero zero three (ON6ZZZ gives his report to W1ZZZ)

thanks W1ZZZ contest (W1ZZZ finishes the contact, identifies and calls CQ contest)

- During some of the larger international contests (CQWW, WPX, ARRL DX, CQ-160m contest – all of these in phone as well as in CW), contest operators not always fully live by the IARU Band Plan. This happens almost exclusively on 160m and 40m, because of the restricted space on those bands. It is nice however to see that during these contests many thousand of hams intensively occupy our bands, which is very positive in view of our required band occupation (use them or lose them). The temporary nuisances caused by this exceptional situation, should best be approached with a positive attitude.

The correct use of QRZ

- QRZ means who called me?, nothing more, nothing less.

- The most classical use of QRZ is after a CQ, when you were unable to copy the call(s) of the station(s) that called you. In a way it means I am sorry, I heard you calling me, but could not get your call. Please call again.

WARNING

It does not mean who’s there? neither does it mean who’s on the frequency? and even less please call me.

- If someone comes on an apparently clear frequency and wants to check whether or not it is in use, he should not use

QRZ?to do that! Just askis this frequency in use?. - If you have been listening to a particular station which has not identified for some time and you would like to know his call, you can ask

your call pleaseorplease identify. Strictly spoken you would need to add your callsign, because you need to identify yourself. - QRZ certainly does NOT mean call me please. We more and more frequently hear CQ calls ending in the word

QRZ. This makes no sense. How can someone already have been calling if you just finished a CQ? - Another incorrect use of QRZ: I am calling CQ in a contest. A station tunes across my frequency and just catches the tail end of my CQ, but missed my callsign. We often hear stations in such circumstances say

QRZ. Totally wrong. Nobody has called this station. All he has to do is to wait for my next CQ to find out my call! The same remark applies to CW of course. - Other similar rather funny but incorrect expressions are:

QRZ is this frequency in use?orQRZ the frequency(should beis this frequency in use?). - One more rather widespread incorrect use of QRZ:

CQ DX CQ this is UR5ZZZ QRZ DX. Just sayCQ DX CQ this is UR5ZZZ calling CQ DX and listening. - Another incorrect use of QRZ:

give me your QRZwhich is supposed to meangive me your call. It is remarkable that in most of the above erroneous uses of QRZ there is a link to the idea of callsign. But please, do use QRZ in the one and only meaning it has: who called me? - During pileups (see § III.1) we will often hear the DX station saying QRZ, not because in the first place he previously missed a call but to tell the pileup he is listening again. This use of QRZ is not quite correct.

Example

CQ ZK1DX ZK1DX calls CQ

ON4YYY you’re 59 ON4YYY calls ZK1DX who replies with a report

QSL QRZ ZK1DX ZK1DX confirms the report (QSL) and adds QRZ, which in this case means I am listening again for the stations calling me rather than who called me? which is the real meaning of QRZ. Although you could argue that he heard other stations before and hence can call QRZ, the use of QRZ followed by ZK1DX is certainly not the most efficient procedure.

What we hear even more and which is completely wrong

QSL QRZ in this case ZK1DX does not identify at all. The pileup wants to know who the DX station is.

The correct and most efficient procedure is as follows

QSL ZK1DX ZK1DX confirms the report he received by saying QSL. This is followed by his call, which is the sign for the pileup to call him.

Check your transmission quality

- Have you properly adjusted your transmitter?

- Is the microphone gain not set too high?

- Is the speech processing level not too high? The background noise level should be at least 25 dB down from your voice peak level. This means that when you don’t speak the output level of the transmitter must be at least approximately 300 times lower than the peak power when you speak.

- Ask a local ham to check your transmission for splatter.

- Having an oscilloscope in line with the output signal so you can monitor for flat topping is the best continuous monitoring system.

The art of telegraphy (CW, Morse code)

- Morse code is a code for transmitting text. The code is made up by sequences of short and long audio tones. A short tone burst is called a DIT, the longer one a DAH. The DAHs are 3 times as long as the DITs. These are frequently but incorrectly called DOTS and DASHES, which make us think of something visual rather than sounds.

- Morse code is not a series of written DOTS and DASHES, although originally, in the 19 th century, Morse code was scribed as DOTS and DASHES on a moving paper strip. Telegraph operators soon found out it was easier to copy the text by listening to the buzz of the scriber machine than trying to read it off the paper strips. So the letter R is not SHORT LONG SHORT nor DOT DASH DOT, nor . - . but DIT DAH DIT.

- In some languages the letter R will be written as DIT DAH DIT, in others as DI DAH DIT. What we are trying to make clear is that there are only two sounds, the short sound (DIT or DI) and the long sound (DAH). Representing two sounds by three words may be confusing; therefore we use only DIT and DAH in this document.

- CW makes extensive use of Q codes, abbreviations and prosigns. These are all shortcuts to make communicating faster and more efficient.

- Hams normally use the word CW for telegraphy. The term CW stems from Continuous Wave although CW is far from being a continuous wave, but rather a wave which is constantly interrupted at the rhythm of the Morse code. Hams use the terms Morse and CW interchangeably – they mean the same thing.

- The -6dB bandwidth of a properly shaped CW signal is approximately 4 times the sending speed in WPM (Words Per Minute). Example: CW at 25 WPM takes 100 Hz (at -6dB). The spectrum required to transmit one SSB (voice) signal (2,7 kHz) can hold more than a dozen CW signals!

- The intrinsic narrow bandwidth of CW results in a much better Signal-to-Noise ratio under marginal conditions as compared to wide band signals such as SSB (a wider bandwidth contains more noise power than a narrower bandwidth). This is why DX contacts under marginal conditions (e.g. working stations in other continents on 160m and working EME) are most frequently done in CW.

- What’s the minimum receiving speed you need to master to be able to regularly make QSOs in Morse code?

- 5 WPM can get you a starter’s certificate, but you will not be able to make many contacts except on the special QRS (QRS means: reduce your sending speed) frequencies. These QRS frequencies can be found in the IARU Band Plan.

- 12 WPM is a minimum, but most experienced CW operators make their QSOs at 20 to 30 WPM and even higher speeds.

- There is no secret recipe to master the Art of CW: training, training, training, just as in any sport.

- CW is a unique language, a language which is mastered in all countries of the world!

The computer as your assistant?

- You will not learn CW by using a computer program that helps you to decode CW.

- It is acceptable though to send CW from a computer (pre-programmed short messages). This is commonly done in contests by the logging program.

- As a newcomer you may want to use a CW decoding program to assist you in order to be able to verify that a text was correctly decoded. However, if you really want to learn the code, you will need to decode the same CW text yourself using your ears and brain.

- CW decoding programs perform very poorly under anything but perfect conditions; our ears and brains are far superior. This is mainly because Morse code was not developed to be automatically sent nor received, as is the case with many modern digital codes (RTTY, PSK etc.).

- A large majority of CW operators use an electronic keyer (with a paddle) instead of a hand key to generate Morse code. It is much easier to send good Morse code using an electronic keyer than with a hand key.

Calling CQ

- What should you do first of all?

- Decide which band you will use. On which band is there good propagation for the path you want to cover? The monthly MUF charts, published in magazines and on many ham websites can be very helpful in this respect.

- Check which band portions are reserved for CW work. On most bands this is at the bottom end of the bands. Consult the IARU Band Plan on the IARU website.

- Listen for a while on the frequency you would like to use to find out whether it is clear or not.

- And then?

- If the frequency seems clear, ask if the frequency is in use. Send

QRL?at least twice, with a few seconds in between. Sending?only is not the proper procedure. The question mark just says I asked a question; the problem is that you did not ask anything. - QRL? (with the question mark) means is this frequency in use?.

- Do not send

QRL? Kas we sometimes hear. It means is the frequency in use? Over to you. To whom? JustQRL?is correct. - If the frequency is in use, someone will answer

R(roger),Y(yes), orR QSY, orQRL,C(I confirm) etc. - QRL (without question mark) means: the frequency is in use. In such a case you will have to look for another frequency to use.

- If the frequency seems clear, ask if the frequency is in use. Send

- And if a clear frequency was found?

- Call CQ. How?

- Send CQ at the speed at which you would like to be answered. Never send faster than you can copy.

CQ CQ G3ZZZ G3ZZZ G3ZZZ AR - AR means end of message or I am through with this transmission, while K means over to you etc. This means you should always terminate your CQ with AR and never with K, because there is nobody there yet whom you can turn it over to.

- Do not end your CQ with AR K: it means end of message, over to you. There is nobody to turn it over to yet. End your CQ with AR. It is true that we often hear AR K on the band, but it is not a proper procedure!

- The use of PSE at the end of a CQ (e.g.

CQ CQ de... PSE K) may seem to be very polite, but is not necessary. It has no added value. In addition, the use of the K is incorrect. Simply use AR at the end of your CQ. - Send your call 2 to 4 times, certainly not more!

- Don’t send an endless series of CQs, with your call just once at the end. Thinking that a long CQ will increase the chances of getting a response is wrong. It actually has the opposite effect. A station that may be interested in calling you first wants to know your call, and certainly is not interested in listening to an almost endless series of

CQ CQ CQ ... - It’s much better to send a number of short CQs (

CQ CQ de F9ZZZ F9ZZZ AR) than one long spun CQ (‘Q CQ CQ ... -15 times- de F9ZZZ CQ CQ CQ ... -15 more times- de F9ZZZ AR). - If you call CQ and want to work split (listening on another frequency than you transmit on), specify your listening frequency at each CQ.

- Send CQ at the speed at which you would like to be answered. Never send faster than you can copy.

Example

End your CQ with UP 5/10... or UP 5... or QSX 1822... (which means that you will listen on 1.822 kHz ). QSX means I listen on ....

Prosigns

Prosigns (short for procedural signs) are symbols formed by combining two characters into one without the inter-character space.

- AR, used to end a transmission, is a prosign.

- Other commonly used prosigns are:

- AS

- CL

- SK

- HH

- BK and KN are not prosigns, as the two letters of these codes are sent with a space in between.

Calling CQ DX

- Just send

CQ DXinstead ofCQ. If you want to work DX from a specific region, call e.g.CQ JA CQ JA I1ZZZ I1ZZZ JA AR(a call for stations from Japan), orCQ NA CQ NA...(a call for stations from North America) etc. You can also make your CQ DX call more explicit by adding that you do not want to contact European stations:CQ DX CQ DX I1ZZZ I1ZZZ DX NO EU AR, but this sounds a little aggressive. - You can also specify a continent: NA = North America, SA = South America, AF = Africa, AS = Asia, EU = Europe, OC = Oceania.

- Even if a station from your own continent calls you, always remain courteous. Maybe he is a newcomer. Give him a quick contact and log him. You may actually be a new country for him!

Calling a specific station (a directive call)

- Let us assume that you want to call DL0ZZZ, with whom you have a sked (schedule, rendez-vous). Here’s how you do this:

DL0ZZZ DL0ZZZ SKED DE G3ZZZ KN. Note the KN at the end, which means you do not want other stations to call you. - If, despite your directive call someone else calls you, give him a quick report and send

SRI HVE SKED WID DL0ZZZ 73....

Carry on and wrap up the CW QSO

- Assume W1ZZZ is answering your CQ:

G3ZZZ DE W1ZZZ W1ZZZ AR, orG3ZZZ DE W1ZZZ W1ZZZ Kor evenW1ZZZ W1ZZZ KorW1ZZZ W1ZZZ AR. - While replying to a CQ, do not send the call of the station you are calling more than once, better still is not to send it at all (you can trust the operator knows his own call...).

- Should the calling station end its call with AR or K? Both are equally acceptable. AR means end of message while K means over to you. The latter sounds a little more optimistic, as maybe the station you call will return for another station...

- There is however a good reason to use AR rather than K. AR is a prosign which means that the letters A and R are sent without any space between them. If one sends K instead of AR and if the letter K is sent somewhat close to the callsign, the letter K may be considered as being the last letter of the call. It happens all the time. With AR this is quite impossible as AR is not a letter. Often no closing code (neither AR nor K) is used, which reduces the risk of making errors.

- Assume you want to reply to W1ZZZ who called you. You can do that as follows:

W1ZZZ DE G3ZZZ GE (good evening) TKS (thanks) FER (for) UR (your) CALL UR RST 589 589 NAME BOB BOB QTH LEEDS LEEDS HW CPY (how copy) W1ZZZ DE G3ZZZ K. This is the time to use K at the end of your transmission. K means over to you, and now the you is W1ZZZ. - Do not end your over with AR K: it means end of message, over to you. It is clear that when you turn it over you have finished your message, no need to say so. End your transmissions (overs) during a QSO with K (or KN when necessary). True, we hear AR K frequently, but it is incorrect.

- The reason for the improper uses of either AR, K, KN, AR K, or AR KN, is that many operators do not really know what each of these prosigns exactly mean. Let’s use them properly!

- We explained that it is not necessary to use the term PSE (please) to end a CQ; do not use it either at the end of your over. So no PSE K or PSE KN. Let’s keep it simple, and leave out the PSE, please...

- On the VHF bands (and higher) it is customary to exchange the QTH-locator. This is a code indicating the geographic location of your station (example: JM12ab).

- The RST report: R and S stand for Readability (1 to 5) and signal Strength (1 to 9) as used for phone signals. The T (1 to 9) in the signal report stands for Tone. It indicates the pureness of the sound of the CW signal, which should sound like a pure sine wave signal without any distortion.

- These original tone ratings attributed to the different T values stem from the early days of amateur radio where often a pure CW tone was an exception rather than the rule. The table below lists the more modern CW tone ratings.

| T1 | 60 Hz (or 50 Hz) AC or less, very rough and broad |

| T2 | Very rough AC, very harsh |

| T3 | Rough AC note, rectified but not filtered |

| T4 | Rough note, some trace of filtering |

| T5 | Filtered rectified AC, but strongly ripple-modulated |

| T6 | Filtered tone, definite trace of ripple modulation |

| T7 | Near pure tone, trace of ripple modulation |

| T8 | Near perfect tone, slight trace of modulation |

| T9 | Perfect tone, no trace of ripple or modulation of any kind |

W4NRL, published in 1995.

- In practice we generally use just a few levels of T with a definition which meets the general status of technology today:

- T1: heavily modulated CW, signs of wild oscillation or extremely rough AC (means: get off the air with such a poor signal!).

- T5: very noticeable AC component (often due to poor regulation of a power supply of the transmitter or amplifier).

- T7 - T8: slightly or barely noticeable AC component.

- T9: perfect tone, undistorted sine waveform.

- Nowadays the most common CW signal deficiencies are chirp and even more common key clicks.

- A long time ago chirp and key clicks were very common problems with CW signals: every CW operator knew that a 579C report meant signals exhibiting chirp, and 589K meant signals with key clicks. Few hams nowadays know what the C and the K at the end of an RST report stand for, so better send

CHIRPorBAD CHIRP, andCLICKSorBAD CLICKSin full words as part of your report. - A typical way to gracefully end the QSO would be:

...TKS (thanks) FER QSO 73 ES (=and) CUL (see you later) W1ZZZ de G3ZZZ SK. SK is the prosign meaning end of contact. DIT DIT DIT DAH DIT DAHis the prosign SK (from stop keying) and not VA as published in some places (SK sent without inter letter spacing sounds the same as VA sent without inter letter spacing).- Do not send

...AR SK. It does not make sense. You are saying end of transmission + end of contact. It is quite obvious the end of your contact is at the end of your transmission. You will quite often hear...AR SK, but the AR is redundant, so avoid using it. - If at the end of the QSO you also intend to close down your station, you should send:

...W1ZZZ DE G3ZZZ SK CL(CL is a prosign meaning closing orclosing down).

Typical CW QSO for the beginner

QRL?

QRL?

CQ CQ G4ZZZ G4ZZZ CQ CQ G4ZZZ G4ZZZ AR

G4ZZZ DE ON6YYY ON6YYY AR

ON6YYY DE W4ZZZ GE TKS FER CALL UR RST 579 579 MY NAME BOB BOB QTH HARLOW HARLOW HW CPY? ON6YYY DE W1ZZZ K

G4ZZZ DE ON6YYY FB BOB TKS FER RPRT UR RST 599 599 NAME JOHN JOHN QTH NR GENT GENT W1ZZZ DE ON6YYY K

ON6YYY DE G4ZZZ MNI TKS FER RPRT TX 100 W ANT DIPOLE AT 12M WILL QSL VIA BURO PSE UR QSL TKS QSO 73 ES GE JOHN ON6YYY DE G4ZZZ K

G4ZZZ DE ON6YYY ALL OK BOB, HERE TX 10 W ANT INV V AT 8M MY QSL OK VIA BURO 73 ES TKS QSO CUL BOB G4ZZZ DE ON6YYY SK

73 JOHN CUL DE G4ZZZ SK

An overview of the closing codes

| Code | Meaning | Use |

|---|---|---|

| AR | End of transmission | At end of CQ and at the end of your transmission when you reply to a station calling CQ or QRZ |

| K | Over to you | At the end of an over and at the end of your transmission when you call a station |

| KN | Over to you only | At the end of an over |

| AR K | End of transmission + over to you | DO NOT USE! |

| AR KN | End of transmission + over to you only | DO NOT USE! |

| SK | End of contact (end of QSO) | At end of QSO |

| AR SK | End of transmission + end of contact | DO NOT USE! |

| SK CL | End of QSO + closing down station | When closing down |

Using BK

- BK (break) is used for switching quickly back and forth between stations without exchanging callsigns at the end of the transmission. In a way it is the CW equivalent of over in phone.

Example

W1ZZZ wants to know the name of G3ZZZ he’s in contact with and sends: ...UR NAME PSE BK. G3ZZZ answers immediately: BK NAME JOHN JOHN BK.

- The break is announced with BK, and the transmission by the correspondent starts with BK. The latter BK however is not always sent.

Still faster

Often even the BK code is not used. One just stops sending (in break in mode, which means that you can listen between words or characters) giving an opportunity to the other station to start sending, just as in a normal face to face conversation, where the word is also passed back and forth without any formality.

Using the prosign AS

If, during a QSO, someone breaks in (transmits his call on top of the station you are working, or gives his call when you switch over), and you want to let him know that you first want to finish the QSO, just send AS (DIT DAH DIT DIT DIT), which means hold on, wait or stand by.

Using KN

- K = over. Sending just K at the end of your over leaves the door open for other stations to break in. If you don’t want to be interrupted, send KN.

- KN means that you want to hear ONLY the station whose callsign you just sent (= go ahead, others keep out or over to you only), in other words: no breakers at this time please.

- KN is mainly used when chaos is around the corner. A possible scenario: different stations are coming back to your CQ. You are decoding one partial call and you send:

ON4AB? DE G3ZZZ PSE UR CALL AGN (again) K. The station ON4AB? answers you, but in addition several other stations call simultaneously, making it impossible to copy his call. The procedure is to call ON4AB? again and end your call with KN instead of K, this to emphasize you only want to hear ON4AB? come back to you.

::tip Example ON4AB? DE G3ZZZ KN or even ONLY ON4AB? DE G3ZZZ KN. If you are still short of authority on the frequency you may try ON4AB? DE G3ZZZ KN N N N (keep some extra space between the letters N). Now you are really getting nervous... :::

How to answer a CQ

Assume W1ZZZ has called CQ and you want to make a QSO with him. How do you go about it?

- Do not send at a higher speed than the station you’re calling.

- Do not send the call of the station you are calling more than once; most of the time the call is not sent, it is obvious who you are calling.

- You can use either K or AR to end your call:

W1ZZZ DE G3ZZZ G3ZZZ KG3ZZZ G3ZZZ KW1ZZZ DE G3ZZZ G3ZZZ ARG3ZZZ G3ZZZ AR-In many cases one sends only the callsign without any closing code (AR or K) at all. This is also common practice in contests.

- Do not end your call with either

...PSE ARor...PSE K.

Someone sends an error in your call

- Assume W1ZZZ has not copied all the letters of your call correctly. His answer is something like:

G3ZZY DE W1ZZZ TKS FOR CALL UR RST 479 479 NAME JACK JACK QTH NR BOSTON BOSTON G3ZZY DE W1ZZZ K. - Now you go back to him as follows:

W1ZZZ de G3ZZZ ZZZ G3ZZZ TKS FER RPRT.... By repeating part of your call a few times, you emphasize this part of the call to get your correspondent’s attention so he can correct the error.

Call a station that’s finishing a QSO

- Two stations are in QSO, the QSO comes to an end. If they both sign with CL (closing down) it means the frequency is now clear as they both closed down. If one or both ended with SK (end of transmission), it may well be so that one or the other will remain on frequency for more QSOs (in principle the station that initially called CQ on that frequency).

- In this case, it is best to wait a while and see if either one calls CQ again.

- Example: W1ZZZ finished a QSO with F1AA:

...73 CUL (see you later) F1AA de W1ZZZ SK. - As neither one calls CQ after the QSO, you can call either one.

- Assume you (G3ZZZ) want to call F1AA. How do you go about it? Simply send

F1AA de G3ZZZ G3ZZZ AR. - In this case calling without mentioning the callsign of the station you want to contact would be inappropriate. Send the call of the station you want to work once, followed by your call once or twice.

Using the = sign or DAH DIT DIT DIT DAH

- Some call it BT, because it is like a letter B and T sent without space (like AR is sent without space), but simply is the equality sign (=) in CW.

- DAH DIT DIT DIT DAH is used as a filler to pause for a second while you think of what you are going to send next. It is also used as a separator between chunks of text.

- As filler it is used to prevent your correspondent from starting to transmit, because you haven’t finished your sentence yet, or you have not finished sending what you want to send. It is clearly the equivalent of euh or eh.

- Some CW operators seem to use DAH DIT DIT DIT DAH spread all over their QSOs as a text separator, to make the text more readable.

Example

W1ZZZ DE G4YYY = GM = TU FER CL = NAME CHRIS QTH SOUTHAMPTON = RST 599 = HW CPI? W1ZZZ DE G4YYY KN. The use of this separation mark seems less common nowadays, and is considered by many as a waste of time. W1ZZZ DE G4YYY GM TU FER CL NAME CHRIS QTH SOUTHAMPTON RST 599 HW CPI? W1ZZZ DE G4YYY KN is as readable as the version of the text with the separators.

Send good sounding code

- Listening to your CW should be like listening to good music, where one never feels like working at deciphering an unknown code or assembling a puzzle.

- Make sure you space letters and words appropriately. Fast sending with a little extra spacing usually makes overall copying easier.

- Experienced CW operators don’t listen for letters but for words. This can of course only be done successfully if the right spacing exists between words. Once you start hearing words instead of a stream of letters, you are getting there! In normal face to face conversation we also listen for words, not for letters, don’t we?

- On an automatic keyer, adjust the DIT/space ratio (weight) correctly. It will sound nicest (most pleasing) if the ratio is a little bit on the high side (DIT a little longer than a space), compared to the standard 1/1 ratio.

Remark

Weight is not the same as DIT/DAH ratio! The DIT/DAH ratio is usually fixed at a 1/3 ratio on most keyers (not adjustable).

I am a QRP station (= low power station)

A QRP station is a station transmitting with a power of maximum 5 W (CW) or 10 W (SSB).

- Never send your call as

G3ZZZ/QRP, this is illegal in many countries (e.g. Belgium). The QRP information is not part of your callsign, so it cannot be sent as a part of it. In many countries the only permitted call suffixes are/P,/A,/M,/MMand/AM.. - If you are really a QRP station, chances are that you will be relatively weak with the station you are calling. Adding unnecessary ballast (the slash and the letters QRP) to your callsign will make it even more difficult to decipher your callsign!

- You can of course always mention during the QSO you are a QRP station, e.g.:

...PWR 5W 5W ONLY.... - If you call CQ as a QRP station and you want to announce that during your CQ, you can do it as follows:

CQ CQ G3ZZZ G3ZZZ QRP AR. Insert a little extra space between the call and QRP and do not send a slash (DAH DIT DIT DAH DIT) between your call and QRP. - If you’re looking for QRP stations specifically, call CQ as follows: ‘CQ QRP CQ QRP G3ZZZ G3ZZZ QRP STNS (stations) ONLY AR’.

The correct use of QRZ?

- QRZ? means who called me?, and nothing else. Use it when you could not quite copy the station (or stations) that called you.

- In CW always send QRZ followed by a question mark (

QRZ?), as is done with all Q codes when used as a question. - Typical use: after a CQ F9ZZZ was unable to decipher any of the callers. Then he sends:

QRZ? F9ZZZ. - If you have been able to copy part of a call (ON4...), and if more stations were calling you, do not send QRZ but rather

ON4 AGN (again) KorON4 AGN KN(KN indicates clearly you only want to hear the ON4 station come back to you). Note that in this case you use K or KN and not AR because you turn it back to one station in particular, the ON4 station whose suffix you missed. Don’t send QRZ in this case or all the stations will start calling you again. - QRZ does not mean who is there? or who is on the frequency?. Assume someone passes by a busy frequency and listens in. After quite a while nobody having identified, he wants to find out the calls. The proper way to do so is to send

CALL?orUR CALL?(orCL?,UR CL?). Using QRZ is inappropriate here. By the way, when you sendCALL?, you should in principle add your call, otherwise you make an unidentified transmission, which is illegal.

The use of ? instead of QRL?

- Before using an apparently clear frequency, you need to actively check if no one is there already (maybe you are not hearing one end of a QSO because of propagation).

- The normal procedure is: send

QRL?(on CW) or askis this frequency in use?on phone. - On CW, some simply send

?, because it is faster and thus potentially creates less QRM if someone else is using that frequency. - But

?can be interpreted in many ways (it says: I am asking a question, but I did not say which one...). Therefore always useQRL?. Merely transmitting a question mark can create a lot of confusion.

Sending ‘DIT DIT’ at the end of a QSO

- At the end of a QSO both QSO partners often send as very last code two DITs with some extra spacing between them (like e e). It means and sounds like bye bye.

Correcting a sending error

- Assume you make a sending error. Immediately stop sending, wait a fraction of a second and send the prosign HH (= 8 DITs). Not always easy to send exactly 8 DITs, you’re already nervous because you made an error, and now they want you to send exactly 8 DITs: DIT DIT DIT DIT DIT DIT DIT DIT, not 7 nor 9!

- In actual practice, many hams send just a few (e.g. 3) DITs, with extra space in between the DITs:

DIT _ DIT _ DIT. These extra spaced DITs indicate that the sender is not sending the code for a letter nor figure. - Resend the word where you made an error and carry on.

- Often even these 3 DITs are left out altogether. When the sender realizes he’s sending an error, he stops for about second and starts sending the same word again.

CW contests

- See § II.8.6 as well.

- Contest means speed, efficiency and accuracy. Hence, send only what’s strictly necessary.

- The most efficient contest CQ is as follows:

GM3ZZZ GM3ZZZ TEST. The word TEST should be placed at the end of the CQ call.- Why? Because anyone tuning across the frequency at the end of your CQ then knows that you call CQ.

- Assume you end your CQ contest call with your callsign: a passer-by noticed he needs that call, but does not know whether you called someone else or called CQ. So he has to wait one more round to find out: a waste of time.

- Therefore, always end your contest CQ with word TEST. Note that even the word CQ is left out from a contest CQ as it contains no additional information.

- An experienced contester will come back to your CQ contest call by just giving his call once. Nothing more. Example:

W1ZZZ. If you don’t get back to him within 1 second, he will likely send his call again unless you returned to someone else. - You copied his call and reply to him as follows:

W1ZZZ 599001orW1ZZZ 5991provided the contest rules admit you to drop the leading zeros. Still faster would be to use cut numbers (abbreviated numbers):W1ZZZ 5NNTT1orW1ZZZ 5NN1. - In most contests the exchange consists of a RST report followed by e.g. a serial number. Do not send anything else. No K at the end, no 73, no CUL (see you later), no GL (good luck); there is no room for all of this in a contest where speed is the name of the game.

- Ideally W1ZZZ will answer e.g. as follows:

599012or5NNT12. - If he did not copy your report he would have sent:

AGN?. As he did not do that, it means that your report was received OK. No need to send TU, QSL, R or whatever else to confirm reception of the report. It is a waste of time. - All that’s left to be done is to end the contact. A polite way of doing this:

TU GM3ZZZ TEST. TU says the QSO is over (thank you), GM3ZZZ identifies you for stations wanting to call you and TEST is a new CQ contest. If the QSO rate is very high, you can leave out the TU. - There are of course slight variations possible, but the key words are speed, efficiency and accuracy.

- Most contesters use a computer contest program, which in addition to logging also allows them to send CW via pre-programmed short messages (CQ, reports etc.). A separate CW paddle and keyer allows for the operator to manually intervene if necessary. Such a setup makes long contests less tiring and will increase accuracy. Contest logging with pen and paper is almost history.

- If you want to look for multipliers or stations you have not yet worked, you will need to scan the band looking for such stations. When you find one, call as follows:

GM3ZZZ. Do not send his callsign, it’s a waste of time. You can be sure the operator knows his own call. And he also knows you are calling him, because of the timing and of the fact that you give your call on the frequency where he is operating! Also, do not sendDE GM3ZZZ, the word DE contains no additional information. - If he does not come back within a second, give your call again, etc.

Example of a CW contest QSO

DL0ZZZ TEST (CQ call from DL0ZZZ)

G6XXX (G6XXX calls DL0ZZZ)

G6XXX 599013 (DL0ZZZ gives G6XXX a report)

599010 (G6ZZZ gives DL0ZZZ his report)

TU DL0ZZZ TEST (DLOZZZ confirms reception and calls CQ Contest)

Abbreviated numbers (cut numbers) used in contests

- The code to be exchanged in most contests consists of a series of numbers, e.g. RST, followed by a 3-digit serial number.

- To save time, the CW code for some numbers (digits) is often shortened (cut):

- 1 = A (DIT DAH, instead of DIT DAH DAH DAH DAH);

- 2, 3 and 4 are usually not abbreviated;

- 5 = E (DIT instead of DIT DIT DIT DIT DIT);

- 6, 7 and 8 are usually not abbreviated;

- 9 = N (DAH DIT instead of DAH DAH DAH DAH DIT);

- 0 = T (DAH instead of DAH DAH DAH DAH DAH);

Example

Instead of sending 599009 one could send ENNTTN. Most frequently you will hear 5NNTTN. As we expect numbers, and although letters are received, we write down numbers. The better computer contest programs allow you to type in letters (in the exchange field); the program will automatically convert these letters to numbers.

- A4 instead of 14 (or a5 instead of 15 etc.): in some contests (e.g. CQ WW) you need to send your CQ zone number as part of the contest exchange. Instead of sending e.g.

59914we often send5NNA4or evenENNA4.

Zero beat

A major advantage of a CW QSO is the narrow bandwidth such a QSO uses (a few hundred Hz), provided both stations in a QSO transmit on the exact same frequency.

- For most standard contacts, both stations will transmit on one and the same frequency (simplex operation). They are said to be zero beat with one another.

- The term zero beat comes from the fact that if two stations transmit on exactly the same frequency, the resulting beat from mixing the two signals would have a frequency of zero Hz: these signals are said to be zero beat.

- Often however, they do not transmit on exactly the same frequency. For this there are two major reasons (often a combination of both):

- One of them is the incorrect use of the RIT (Receiver Incremental Tuning) on the transceiver. Most modern transceivers have an RIT function which makes it possible to listen on a frequency which is (slightly) different from the transmit frequency.

- A second reason is that the operator does not apply the correct zero beat procedure. With most modern transceivers the zero beat procedure consists of making sure that the pitch of the side tone (CW monitor signal) of the transmitter is at exactly the same frequency as the tone (pitch) of the station you listen to. If you listen at 600 Hz and the side tone pitch is set at 1.000 Hz, you will transmit 400 Hz away from the station you are calling.

- On modern transceivers the frequency of the CW side tone monitor (pitch) is adjustable, and tracks the BFO frequency offset.

- Many experienced CW operators listen at a fairly low beat tone (400 – 500Hz, sometimes even as low as 300 Hz) instead of the more usual 600 – 1,000 Hz. For most people a lower pitch frequency is less tiring during long periods of listening and, in addition it allows for better discrimination between close spaced signals.

Where can one find slow speed CW stations (QRS)?

| Band | Frequency (kHz) |

|---|---|

| 80m | 3 550 – 3 570 |

| 20m | 14 055 – 14 060 |

| 17m | 18 095 – 18 105 |

| 15m | 21 055 – 21 060 |

| 10m | 28 055 – 28 060 |

- QRS means send slower;

- QRQ means send faster.

Do I have key clicks?

Not only the content and the format of what you send needs to be OK ... but also the quality of the CW signals you transmit must be good. Quality problem #1 is key clicks.

- Key clicks are always shown by the envelope waveform of the transmitted signal looking like a (nearly) perfectly square wave, with no rounded off edges, often including overshoot leading end spikes. All of this results in wide sidebands, which are witnessed as clicks left and right of the CW signal. There are three main technical causes for this problem:

- One is an improperly shaped keying waveform containing a lot of harmonics (square edges). The cause of this is most often a poor circuit design by the manufacturer. Fortunately, a number of circuit changes have been published on internet to solve these problems.

- The second one is having too much driving power to the amplifier combined with improper ALC (automatic level control) action (too slow attack time), resulting in leading edge spikes. It is always recommended to manually adjust the required drive power and not to rely on action of an ALC circuit.

- A third one is improper open/closure sequence timing of RF relays in full break in.

- How can you detect key clicks generated by your own station? A well experienced ham in your close neighbourhood can listen carefully for clicks.

- Much better is to continuously monitor all transmissions using an oscilloscope displaying the waveform of your transmitted signal.

- Note that even some of the popular fairly recent commercial transmitters have outspoken key clicks.

- If you notice key clicks on your transmission or if you get reports on excessive key clicks, correct the problem or find help to do so. Your key clicks are causing problems with your other hams. Hence getting rid of your key clicks is a question of ethics!

Too fast?

Is the CW speed you master not high enough to be able to make many QSOs?

- To increase your receiving speed, you need to exercise at a speed which is at the limit of your capabilities, where you gradually and constantly increase the speed (à la RUFZ.

- Up to approx. 15 WPM you can write down a text sent in CW letter by letter.

- At over 15 or 20 WPM you should recognize words, and write down only what’s essential (name, QTH, WX, power, antenna etc.).

CW training software

- UBA CW course on the UBA-website

- G4FON Koch method trainer

- Just learn Morse code

- Contest simulation

- Increase your speed using RUFZ

- etc.

A few important hints

- Never learn CW by counting DITs and DAHs...

- Never learn CW by grouping together similar characters (e.g. e, i, s, h, 5): this will make you count DITs and DAHs forever!

- Never describe the CW code for a character using the words dot and dash but rather using the words DIT and DAH. Dots and dashes make us think of something visual, DITs and DAHs make us rather think of sounds.

Most used CW abbreviations

| AGN | again |

| ANT | antenna |

| AR | end of message (prosign) |

| AS | wait a second, hold on (prosign) |

| B4 | before |

| BK | break |

| BTW | by the way |

| CFM | (I) confirm |

| CL | call |

| CL | closing (down) (prosign) |

| CQ | general call to any other station |

| CU | see you |

| CUL | see you later |

| CPI | copy |

| CPY | copy |

| DE | from (e.g. W1ZZZ de G3ZZZ) |

| DWN | down |

| ES | and |

| FB | fine business (good, excellent) |

| FER | for |

| GA | go ahead |

| GA | good afternoon |

| GD | good |

| GD | good day |

| GE | good evening |

| GL | good luck |

| GM | good morning |

| GN | good night |

| GUD | good |

| HI | laughter in CW |

| HNY | Happy New Year |

| HR | here |

| HW | how (e.g. HW CPY) |

| K | over to you |

| KN | over to you only, go ahead please and others keep out |

| LP | long path (propagation) |

| LSN | listen |

| MX | Merry Christmas |

| N | no (negation) |

| NR | number |

| NR | near |

| NW | now |

| OM | old man (male ham) |

| OP | operator |

| OPR | operator |

| PSE | please |

| PWR | power |

| R | roger, yes, I confirm, received |

| RCVR | receiver |

| RX | receiver |

| RIG | equipment |

| RPT | repeat |

| RPRT | report |

| SK | end of contact (prosign) |

| SK | silent key, a deceased ham |

| SP | short path (propagation) |

| SRI | sorry, excuse me |

| TMW | tomorrow |

| TMRW | tomorrow |

| TKS | thanks |

| TNX | thanks |

| TRX | transceiver |

| TU | thank you |

| TX | transmitter |

| UFB | ultra fine business |

| UR | your |

| VY | very |

| WX | weather |

| XMAS | Christmas |

| XYL | wife, spouse, ex-young lady |

| YL | young lady |

| 51 | CB slang. Do not use it. |

| 55 | CB slang. Do not use it. |

| 73 | best regards |

| 88 | love and kisses |

WARNING

73 is also commonly used in phone: never say or write 73s, best 73 or best 73s; all of these are corruptions. Say seventy three and NOT seventy threes.

SUMMARY (most important Q codes and prosigns)

| AR | end of transmission: indicates the end of a transmission which is not addressed to anyone in particular (e.g. at the end of a CQ) |

| K | over to you: ends a transmission of a conversation between 2 or more stations. |

| KN | over to you only: similar to K but you emphasize you do not want to hear any other callers or breakers. |

| SK | end of QSO: is used to end a QSO (SK = Stop Keying). |

| CL | closing down station: last code sent before closing down your station (CL = closing down) |

| QRL? | is the frequency in use?: you must always use it before calling CQ on a new frequency. |

| QRZ? | who called me?: QRZ has no other meaning. |

| QRS | reduce your sending speed |

| AS | just a moment, hold on... |

| = | I am thinking, hold on, uh... (also used as a separator between portions of text) |

Other modes

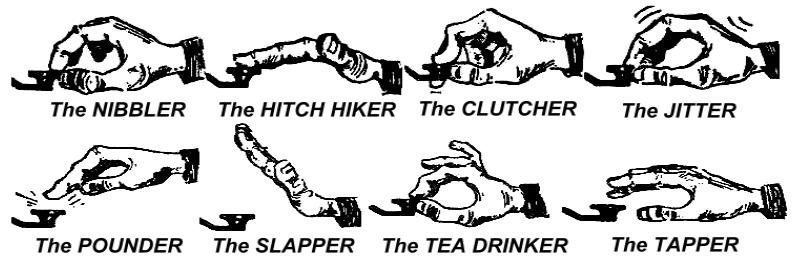

So far we have discussed operational behavior for phone and CW operating in great detail, as these are by far the most frequently used modes in amateur radio. You will have noticed that general operational behavior is very similar in both modes, and differences are mainly due to the use of the Q code, prosigns and other specific terminologies.

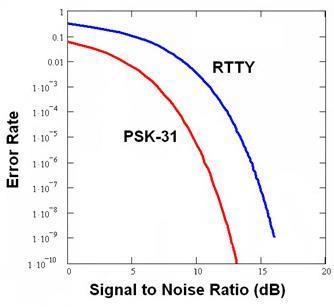

The basic procedures as outlined for phone and CW apply to most of the otherfrequently used modes, such as RTTY, PSK(31), SSTV etc.

Radio amateurs also use highly specialized modes such as Fax, Hell (schreiber), contacts through satellites, EME (moonbounce, Earth Moon Earth), meteor scatter, Aurora, ATV (wideband amateur television), etc., which, to a certain extent, may call for specific operational procedures.

In the next few pages we will cover some of these other modes.

RTTY (Radioteletype)

What is RTTY?

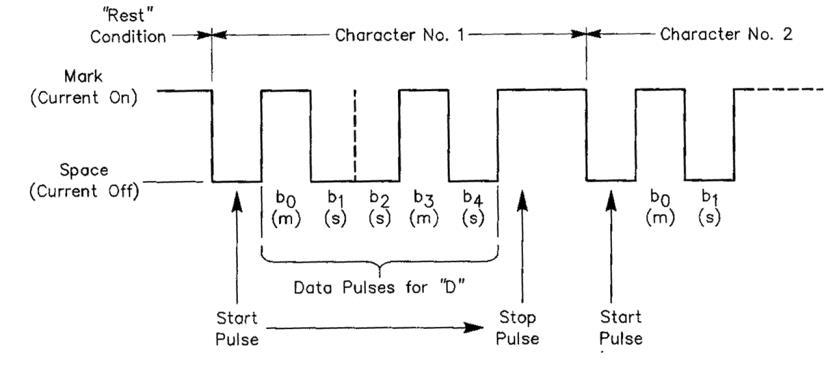

- RTTY is the oldest of the digital modes used by hams, if you exclude CW, which really is also a digital mode. RTTY is used to send and receive text. The code used in RTTY was developed to be generated and decoded by a machine. In the old days (the days of Telex machines), these were mechanical machines that generated and decoded the Baudot code, which is the original teleprinting code invented in 1870! Each character typed on the machine keyboard is converted to a 5 bit code, preceded by a start bit and followed by a stop bit. With 5 bits one can, however, only obtain 32 possible combinations (25 = 2x2x2x2x2). As we have 26 letters (in RTTY only uppercase letters are available) plus 10 figures and a number of signs, the Baudot code has given 2 different significations for each 5 bit code, which depend on the state the RTTY machine is in. These states are the so-called LETTERS and FIGURES states. If the machine is sending letters, and needs to send figures, it will first send a 5 bit code corresponding to FIGURES. This code will set the machine (or software) in the FIGURES state. If this code is not received, the following figures will be printed as (the equivalent code) letters. This is a frequently occurring error that all RTTY operators are well acquainted with, e.g. while receiving the RST report (

599is received asTOO). Nowadays, RTTY is almost exclusively generated using a PC with sound card, using dedicated software.

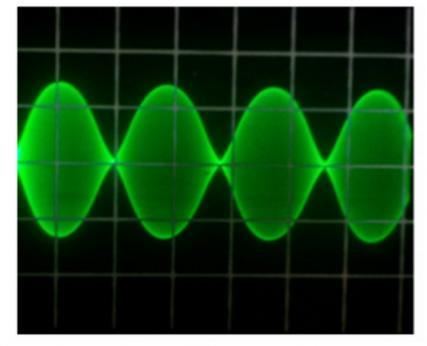

On the amateur bands the Baudot code is transmitted by FSK (Frequency Shift Keying). The transmitter carrier is shifted 170 Hz between on and off (called mark and space in RTTY). In the early days of RTTY the shift was 850 Hz. The Baudot code does not contain any error correcting mechanism. The standard speed used on the amateur bands is 45 Baud. Using a 170 Hz shift, the –6dB bandwidth of the FSK signal is approximately 250 Hz.

As RTTY is simply the shifting of a (constant) carrier, the duty cycle of the transmitted signal is 100% (versus approximately 50% in CW and 30 to 60 % in SSB depending on the degree of speech processing). This means that we shall never push a 100 W transmitter (100 W in SSB or CW) over 50 W output in RTTY (for transmissions lasting longer than a few seconds).

RTTY frequencies

Before 2005, IARU subdivided the various ham bands by modes (phone band, CW band, RTTY band etc.). As the Band Plan since 2005 is based on transmitted signal bandwidth rather than mode, the Band Plan can be quite confusing for newcomers and old timers alike.

We therefore have listed the range of frequencies which are most frequently used for each mode. These frequencies may be slightly different from what you find in the IARU Band Plan in as far as we can compare modes with bandwidth, which is not always obvious. The table below is not meant to replace the IARU

| Band | Frequency (kHz) |

|---|---|

| 160m | 1 838 – 1 840 |

| 80m | 3 580 – 3 600 |

| 40m | 7 035 – 7 043 |

| 30m | 10 140 – 10 150 |

| 20m | 14 080 – 14 099 |

| 17m | 18 095 – 18 105 |

| 15m | 21 080 – 21 110 |

| 12m | 24 915 – 24 929 |

| 10m | 28 080 – 28 150 |

Very little RTTY on 160m. Stay with the entire signal in this window. USA: 1800 – 1810 kHz (not allowed in Europe) Japan: 3525 kHz

Specific operational procedures

- All standard phone and CW procedures apply.

- RTTY is extremely sensitive to QRM (all kinds of interferences). Pileups must be run in the split frequency mode (see § III.1).

- The Q codes were originally developed for use in CW. Later, hams started using a number of these codes in phone, where they have been widely accepted. One can of course also use these Q codes in the newer digital modes such as RTTY and PSK (See § II.10.2) rather than to develop another set of codes of their own, which would inevitably lead to confusion.

- In the digital modes all computer programs provide the facility to create files with short pre packaged standard messages that can be used in a QSO. An example is the so-called brag tape that sends endless information about your station and your PC. Please do not send all these details unless your correspondent asks for it. A brief

TX 100 W, and dipolewill be sufficient in most cases. Just give information your correspondent could be interested in. Don’t end your QSO by sending the time, the number of the QSO in your log etc. This is worthless information. Your correspondent also has a clock and he does not care how many QSOs you have already made. Respect your correspondent’s choice, and don’t force him/here to read all that garbage.

Nominal transmit frequency on RTTY

- Two definitions were made long time ago:

- The frequency of the mark signal determines the nominal frequency of an RTTY signal.

- The mark signal must always be transmitted on the highest frequency.

- If we listen to an RTTY signal, how can we tell which of the 2 tones is the mark signal? If you receive the signal on USB (upper sideband), the mark signal is the signal that has the higher audio tone. In LSB it is, obviously, the other way around.

- RTTY usually employs one of three methods to be generated in a transmitter:

- FSK (Frequency Shift Keying) the carrier is shifted according to modulation (mark or space). RTTY is actually FM. All modern transceivers have an FSK position on the mode selector switch. These transceivers all indicate the correct frequency on the digital display (being the mark frequency), provided that the modulating signal (the Baudot code) is of the correct polarity. You can usually invert the logic polarity either in your RTTY program or on your transceiver, or both (positions normal and reverse). If not set correctly, you will be transmitting upside down.

- AFSK (Audio Frequency Shift Keying) in this method the Baudot code modulates a generator which produces two audio tones, one for mark and one for space. These audio tones must fall within the audio passband of the transmitter. Modern RTTY programs on a PC generate these two tones using the soundcard. These tones serve to modulate the transmitter in SSB.

- on USB: in this method the transmitter, in upper sideband position, is modulated by the AFSK audio tones. Assume you transmit on 14090 kHz (zero beat frequency or suppressed carrier frequency on SSB). If you modulate your transmitter with two audio tones being e.g. 2295 Hz for mark and 2125 Hz for space, the mark signal will be transmitted on 14 092 295 Hz and the space signal on 14 092 125 Hz. This agrees with the definition given above (mark → highest frequency). Watch out, your transmitter will indicate 14.090 kHz on its dial! In other words, if properly modulated (tones not inverted) and when using 2.125 Hz (space) and 2.295 Hz (mark) as modulation tones, you simply add 2.295 Hz to the SSB dial reading (the nominal SSB frequency) of your transceiver to obtain the nominal RTTY frequency.